Scriptorium Daily

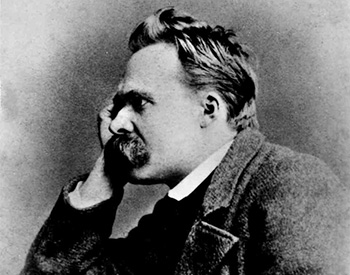

God was dead, to begin with. If you want to understand the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), you have to start where he started, with the premise that there is no God, and that Christian monotheism had all been a big mistake. As far as Nietzsche was concerned, the best thinkers of the mid-nineteenth century had altogether undermined Christian truth claims: Strauss’ Life of Jesus Critically Examined (1846) and Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity (1855) were among the important books that had settled things (two books, by the way, which novelist George Eliot made sure to translate so they could have their effect for English readers). By the 1880s, anybody who still clung to Christianity was either not paying attention, or was fooling themselves. The master of melodrama and bombast in the intellectual life, Nietzsche looked back on recent Western thought and said, “We have become God’s murderers.”

God was dead, to begin with. If you want to understand the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), you have to start where he started, with the premise that there is no God, and that Christian monotheism had all been a big mistake. As far as Nietzsche was concerned, the best thinkers of the mid-nineteenth century had altogether undermined Christian truth claims: Strauss’ Life of Jesus Critically Examined (1846) and Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity (1855) were among the important books that had settled things (two books, by the way, which novelist George Eliot made sure to translate so they could have their effect for English readers). By the 1880s, anybody who still clung to Christianity was either not paying attention, or was fooling themselves. The master of melodrama and bombast in the intellectual life, Nietzsche looked back on recent Western thought and said, “We have become God’s murderers.” So God was dead as a coffin-nail, and Nietzsche knew it. He also knew that the educated people of his day knew it. But what bothered him was that they didn’t act like it. Though sound scholarship had demolished Christian theology, Christian morality was still alive and well. So Nietzsche appointed himself the official whistle-blower on the death of God, and like many of the radicals of the late nineteenth century, he insisted that we should follow out the logic of godlessness to its conclusions. The very people who had spent the nineteenth century driving God out of their worldviews were failing to draw the necessary conclusions about their morality. Even without God, they held on to absolute truth, to reason, to the binding claims of right and wrong. Worst of all, the godless moderns still had a conscience, and it continued to condemn them when they violated its dictates. He spent half his time reminding moderns that they had no right to hold on to the benefits of monotheism after murdering God, and the other half of his time rejoicing that there was no longer any ground for conscience to stand on.

“If God is dead, anything is possible,” mused Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor in 1880’s The Brothers Karamazov, and it was Friedrich Nietzsche who set himself to the task of showing what that meant for morality. Since morals didn’t come from a God, where did they come from? He answered that question in 1887 with his Genealogy of Morals, which is the best, and by far the clearest, introduction to Nietzsche’s overall project. In short, the first essay in the three-part Genealogy argues that morality itself, the whole idea of good versus evil, came about when weak people figured out a way to make strong people feel bad about being strong. The reason we feel that we should take pity on the weak, or feel bad for imposing our wills on others, is that long ago, in some dark, underground workshop of the spirit, the weak had invented “morals” to compensate for their weakness. Instead of just straightforwardly hating their enemies, they declared that their superiors stood under the judgement of a higher authority, God, whose law condemned them. And then, amazingly, they had convinced the strong to accept these twisted ideals as The Way Things Ought To Be. This was the slave-revolt at the beginning of the epoch of morality, and the slaves have been in charge ever since.

Until Nietzsche, that is, who claimed to be writing with a prophetic voice that announced a new, natural way of valuing things: Whatever affirms and perpetuates life is good, and whatever denies or suppresses life is bad. All of this has to be read in Nietzsche’s own words, though, because they are so powerful (“I can write in letters which make even the blind see,” he wrote) and because it’s important to keep Nietzsche’s own brand of Life After God separate from the other brands. He does not fit the categories of bleak existentialism, for example, offering instead a more positive account of the human place in the world. He was not a Darwinist: he was fine with Darwinism’s materialism, but thought its optimism about inevitable progress was something only an Englishman could have imagined and only Germans could have believed. He was not a proto-Nazi: he hated German nationalism at least as much as he hated Jews. But the Nietzschean influence has not diminished as the world has moved from the modern era into the post-modern. His work has influenced most of the thinkers whose names make up the reading list for an introductory class on postmodernism: Barthes, Derrida, Foucault, Lacan, Deleuze, Baudrillard, and Lyotard.

Christian readers have trouble engaging Nietzsche because, to state the obvious, they don’t share his presupposition that the arguments of Victorian atheism were in fact conclusive. They would like to reserve the right to go back and have those arguments about truth. But as hard as he is to engage, Nietzsche is well worth coming to terms with for several reasons. He pioneered the strategy of discrediting Christianity by ignoring the question of its truth, in order to cut straight to his major complaint: Christianity is bad for human beings and other living things like the mind, the arts, and freedom. That attitude is probably the dominant tone of popular atheism in our time.

Nietzsche is also the one whose systematic, genealogical suspicion towards the whole vocabulary of Christian virtue (love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control) has burned away so much of the credibility of Christianity. Christianity has always been called into question by the bad conduct of its adherents. But Nietzsche (who grew up in a pastor’s home and maintained a commitment to Christ well into his teens) transformed that anecdotal criticism into a wholesale deconstruction of Christianity. Genealogy of Morals is the book where he did that, and if this book is right, then every word of the New Testament is a mendacious lie. At least all the significant nouns.