Scriptorium Daily

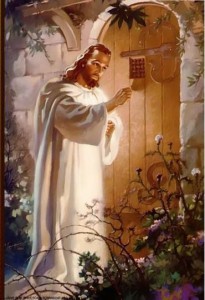

“Behold, I stand at the door and knock,” says the risen Lord to the Laodicean church (Revelation 3:20). There is an evangelical tradition of using this verse’s imagery in evangelism, and Dan Wallace recently gave some attention to this notion of telling unbelievers to ask Jesus into their hearts. The bottom line is, according to Wallace, that’s not what the verse means in context (it’s a message to a church, not individual unbelievers) or in Greek (he distinguishes, somewhat subtly, between “come in to” and “come into”). Wallace also talks about the mis-understandings that might arise from the over-use, in some circles apparently even the exclusive use (!), of this idea that conversion is a matter of admitting Jesus into your heart. Vintage Dan Wallace, go and read.

“Behold, I stand at the door and knock,” says the risen Lord to the Laodicean church (Revelation 3:20). There is an evangelical tradition of using this verse’s imagery in evangelism, and Dan Wallace recently gave some attention to this notion of telling unbelievers to ask Jesus into their hearts. The bottom line is, according to Wallace, that’s not what the verse means in context (it’s a message to a church, not individual unbelievers) or in Greek (he distinguishes, somewhat subtly, between “come in to” and “come into”). Wallace also talks about the mis-understandings that might arise from the over-use, in some circles apparently even the exclusive use (!), of this idea that conversion is a matter of admitting Jesus into your heart. Vintage Dan Wallace, go and read. Wallace is trying to solve a problem of reductionism, I think. He hears people reducing the richness of the biblical view of salvation to a decontextualized formula which has become trite from over-use, and which therefore doesn’t often succeed in pointing us back to what it’s really all about.

I took a different approach to the same problem in my new book, when I studied the way evangelicals talk. My goal was to do some digging, to see if there might be a robust trinitarian theology buried under some of our favorite formulas.

“Jesus in my heart” was one I was especially eager to investigate. What I found was a trail that goes from the flannelgraph gospel presentations, back through Billy Graham and Robert Boyd Munger to one of the great Puritan theologians, and trinitarian gold all the way along the path. We definitely need to watch what we say. But part of that watching involves knowing our own history, and sympathetically understanding why we originally started saying what we say.

Here’s an excerpt on the subject, from The Deep Things of God: How the Trinity Changes Everything, Chapter 5, “Into the Saving Life of Christ”

The problem is not in being too Christ-centered, but in using Christ-centeredness to enable an unbiblical Father-forgetfulness.

An example is the tendency to think of Jesus as the one who lives in our hearts, without making reference to the Holy Spirit’s role as the direct agent of indwelling. There is a grain of truth to this: Jesus does dwell in the hearts of believers, and a handful of passages in the New Testament describe our relationship to Jesus this way (especially Ephesians 3:16-17). But the dominant message of the Bible is that we are in Christ, not that Christ is in us. And on those few occasions when Christ is said to be in us, the work of the Spirit is nearly always mentioned. This is not a theological subtlety noted only by overly-precise theologians, but a special emphasis of Scripture.

Billy Graham, who has certainly popularized a powerful message about accepting Jesus into your heart, identified this indwelling work of the Spirit in salvation as something that needed special emphasis:

One point about the relation of the Holy Spirit and Jesus Christ needs clarification. The Scriptures speak of ‘Christ in you,’ and some Christians do not fully understand what this means. As the God-man, Jesus is in a glorified body. And wherever Jesus is, His body must be also. In that sense, in His work as the second person of the Trinity, Jesus is now at the right hand of the Father in heaven…. For example, consider Romans 8:10 (KJV), which says, “If Christ is in you, the body is dead because of sin.” Or consider Galatians 2:20, “Christ lives in me.” It is clear in these verses that if the Spirit is in us, then Christ is in us. Christ dwells in our hearts by faith. But the Holy Spirit is the person of the Trinity who actually dwells in us, having been sent by the Son who has gone away but who will come again in person when we shall literally see Him.

Once again, it is not wrong to affirm that Jesus lives in our hearts, but it is wrong to ignore the Holy Spirit’s role in that indwelling.

It is interesting to see how this signature evangelical teaching about Christ living in our hearts has devolved and degraded over the years. If you trace it to its origin, it is a relentlessly trinitarian message, as we have already seen in Billy Graham’s presentation of it in the 1970s.

An earlier presentation of the message of Jesus in our hearts, and one that the Billy Graham team made extensive use of, is Robert Boyd Munger’s widely-reprinted 1951 sermon, My Heart –Christ’s Home. Munger begins with Ephesians 3:16-17, and then says, “Without question one of the most remarkable Christian doctrines is that Jesus Christ himself through the Holy Spirit will actually enter a heart, settle down and be at home there. Christ will live in any human heart that welcomes him.”

Munger definitely describes the indwelling of Christ as being “through the Holy Spirit” in this opening sentence. In the next few pages, he describes Christ’s ascension and the subsequent descent of the Spirit which made the indwelling possible: “Now, through the miracle of the outpoured Spirit, God would dwell in human hearts.” From this clearly Spirit-honoring beginning point, Munger goes on to develop the homey application that made his sermon a classic, as Christ the guest is shown through each room of the heart-house, extending his lordship into every part.

Even that element of Munger’s sermon can be traced further back, to John Flavel’s 1689 book Christ Knocking at the Door of Sinners’ Hearts, or, A Solemn Entreaty to Receive the Saviour and His Gospel. Flavel, whose radically and consistently trinitarian theology we have seen in the previous chapter, places Jesus decidedly in the context of the Father and the Spirit. Flavel’s book is even based (like Munger’s) on Jesus’ saying in Revelation 3:20, “Behold, I stand at the door and knock.” He carefully distinguishes the original intention of that passage (a warning to a church) from its legitimate extended sense (a personal invitation to sinners), and then dilates on the personal application: “Thy soul, reader, is a magnificent structure built by Christ; such stately rooms as thy understanding, will, conscience, and affections, are too good for any other to inhabit.”

With the trinitarian background in place, the message of Jesus knocking on the door of a sinner’s heart is a recognizably trinitarian gospel. It is not Father-forgetful or Spirit-ignoring in its classic exponents such as John Flavel, Robert Boyd Munger, or Billy Graham. Surely these three witnesses count as an evangelical pedigree, and can bolster our confidence in the theology presented through countless flannel-graph images of Christ knocking on the door of a fuzzy, felt heart-house. Surely with this trinitarian lineage in place, we can affirm that all the flannel-graphs are true! But we have to admit that the trinitarian connections are fairly easy to lose. They may have been there in Flavel, Munger, and Graham, but they are often lost in translation, especially in recent decades. Jesus is still presented as knocking on the heart’s door, but too often in a Father-forgetful and Spirit-ignoring way.

Just as we can lapse into substituting Jesus for our heavenly Father, we can replace the Spirit with Jesus when we talk about the divine indwelling. Taken together, these two errors constitute an unfortunately common distortion of the biblical message. They replace the Trinity with Jesus, or they center on Jesus in a Father-forgetful, Spirit-ignoring manner. Jesus becomes my heavenly Father, Jesus lives in my heart, Jesus died to save me from the wrath of Jesus, so I could be with Jesus forever.

Once again, there is no such thing, in Christian life and thought, as being too Christ-centered. But it is certainly possible to be Father-forgetful and Spirit-ignoring. At their best, and from their roots, evangelicals have avoided that. In recent decades, though, it requires vigilance to make sure we are presenting the evangelical message with recognizable trinitarian connections.

What Would Jesus Do? He would do the will of the Father in the power of the Spirit. He would send the Spirit to bring us to the Father.