by Robert Louis Wilken

First Things

Since the Enlightenment it has been fashionable to denounce Christians for prostituting the legacy of classical culture. Edward Gibbon wrote that Christians had “debased and vitiated the faculties of the mind” and “extinguished the hostile light of philosophy and science” that had shone brightly in the ancient world. Gilbert Murray, a classicist of the early twentieth century, echoed Gibbon: “Truth was finally made hopeless,” he wrote, “when the world, mistrusting Reason, wary of arguments and wonder, flung itself passionately under the spell of a system of authoritative Revelation, which acknowledged no truth outside itself and stamped free inquiry as sin.” Murray mourned the consequences: “The intellect of Greece died ultimately of that long discouragement which works upon nations like slow poison.”

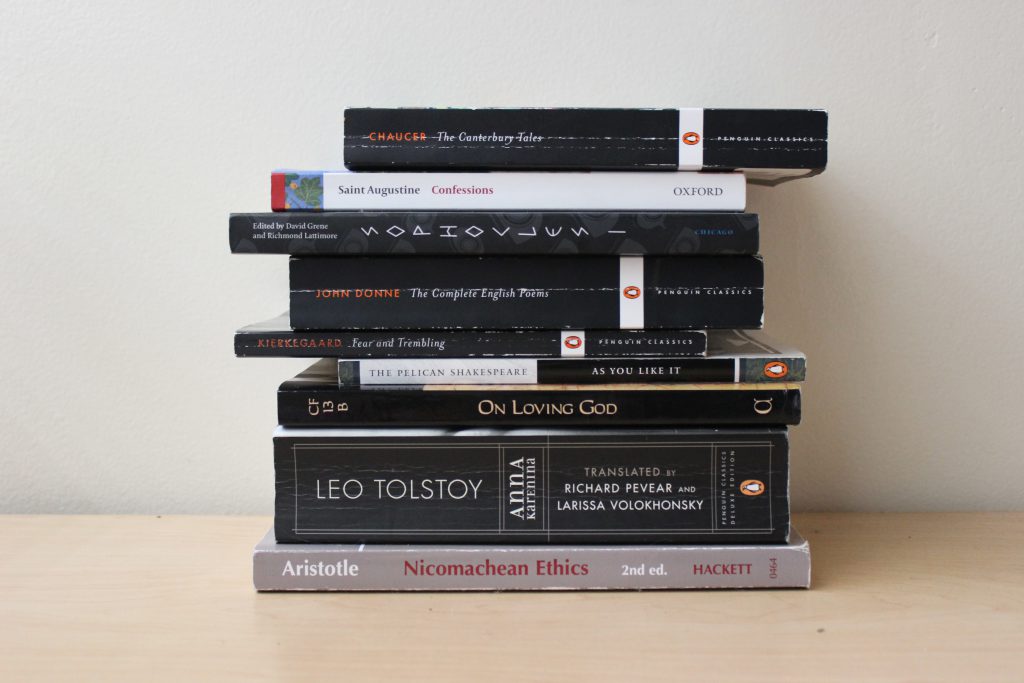

It is ironic that the intellectual hubris of these judgments (which in a moment of generosity might be called intemperate) would have been impossible without access to Greek and Latin sources prior to Christianity. When Christianity became ascendant in the early Middle Ages, the books of the Greeks and Romans were copied and transmitted to later generations, thereby preserving the wisdom and learning of antique culture largely intact and providing the very basis on which Gibbon, Murray, and others formulated their attacks on Christendom.

In some civilizations the relation between religion and culture is so intimate that it is impossible to disentangle the one from the other, or to trace the separate sources that gave rise to distinctive forms of social and spiritual life. Christianity, however, does not fit comfortably into this pattern. Even though many different streams flowed into the great river that is Christian history, some of the sources that gave rise to Christian culture were already mighty torrents before they became part of the new civilization. In his provocative book

Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization (2009), Rémi Brague calls this dependency on an earlier culture

secondarity. By this term he means not simply that an earlier culture is given as a historical fact, but that those who come later honor and cherish what went before.

Secondarity was evident among the ancient Romans who received and admired the cultural accomplishments of the Greeks and made them their own. But secondarity was no less a characteristic of the early Christians. When they first began to adorn the walls of the catacombs with pictures, they drew freely on the artistic traditions of the ancient world. They appropriated, for example, two familiar images from Greco-Roman culture: the

kriophoros, or lamb bearer (what appears to us as the good shepherd), which represented

philanthropia; and the

orant, a figure with hands uplifted in a gesture of prayer that symbolized piety.

In other paintings artists depicted people and events that are recognizably biblical, such as the figure of Jonah, but the visual vocabulary was taken from Roman art. The painter, whether a Christian or a skilled pagan hired for the task, did not draw the figure of Jonah cold, with merely the text of the Bible before him. He exploited a repertory of stock models that were known to Roman artists. The image of Jonah under the broom tree is a Christian version of the familiar figure of Endymion, a handsome young man with whom the goddess Selene fell in love. In Greek art Endymion was depicted sleeping in a cave, where he was visited periodically by his lover. Christians adopted the image of the sleeping Endymion to depict Jonah, painting it on the walls of catacombs and carving it on Christian sarcophagi.

Another figure familiar in early Christian art is the Greek singer Orpheus with his lyre. He is clothed in a short tunic, wears a Phrygian cap, and is surrounded by wild beasts. In Greek myth Orpheus had a voice of such sweetness that no one could resist his melodies. He met and wooed the young maiden Eurydice, but their joy was brief. Shortly after they were married, she died from a serpent’s bite. Determined to free his beloved from the land of the dead, Orpheus went down into Hades and so charmed the netherworld with his singing that he won her release, but on the condition that as he led her to the land of the living, he would not look back at her. At the very end of the journey, he turned to see whether Eurydice was behind him—and lost her forever. He then forsook the company of human beings and retired to the woods near his home in Thrace, in northern Greece, where his mournful song enchanted the trees and rivers and tamed the wild animals.

Although Christian writers seldom drew on ancient myths to interpret the person of Christ, one Christian writer, Clement of Alexandria, thought the parallel between Orpheus and Christ was fitting. Orpheus, a skilled master of his art, pacified wild beasts by the power of his song, but Christ’s new song, says Clement, is able to tame “the most intractable of all animals—man.”

A different kind of example of secondarity is the Christian reception of Roman law. When, in the sixth century, the Christian emperor Justinian undertook a revision of Roman law, he had his legal scholars collect statutes going back to the time of Hadrian, a pagan emperor, in the second century. Justinian’s lawyers recognized that law has its own integrity and independence, and the influence of Christian beliefs and ideas on the

Corpus Iuris Civilis is slight. There is little evidence of a systematic effort to Christianize the substantive principles of classical Roman law. Much later, at Bologna in the Middle Ages, Christian legal scholars based their work on Roman law, the legal system of an earlier civilization.

Secondarity is not characteristic of all Christian cultures. When Christianity arrived in Armenia in the fourth century, there was no written culture. Armenian “literature” was made up of heroic oral epics. Christianity could not exist without books, and, after some experimentation with different alphabets, the resourceful and enterprising monk Mastoc created, with heavenly inspiration and the skills of a calligrapher, a body of letters that suited the Armenian language. At once he put several of his students to the task of translating the Bible into Armenian, beginning, curiously, with the Book of Proverbs. Latin-speaking Christians in North Africa learned their letters reading Virgil or Horace; Armenian Christians learned theirs reading the Bible. As a consequence Armenian culture

was Christian culture, with no prior tradition to build on or play off against that of the Church. In like manner, in the ninth century, when the apostles to the Slavs, Cyril and Methodius, devised an alphabet to write down the Slavic language, they laid the foundation for a Slavic Christian culture.

In the West, however, secondarity has been the rule. And although preserving what had come before made Christianity vulnerable to critique from within, drawing inspiration from the ancient books it used and cherished also provided the Church with intellectual resources to create a new civilization that drew on the wealth of the old—the “spoils of Egypt,” as Origen of Alexandria called the appropriation of Greek wisdom. Christianity was born in a world with a mature and fully developed culture, an established educational system, a canon of literary classics, sophisticated philosophical traditions, a coherent understanding of the moral life, an inheritance of art and architecture, and law and politics. It is a remarkable experience, one that never fails to astonish, to visit the ruins of the Roman Empire that can be found all over the Mediterranean world. From Tunisia in the west to Syria in the east, from Italy on the north shore to Libya on the south, in Turkey and the Balkans, in France and in Spain, one finds the remains of cities whose beauty and grace and grandeur fill the observer with awe and wonder.

Not only are some of the buildings still standing (the theater at Ephesus is a spectacular example), but the books—among them the

Aeneid of Virgil and the

Lives of Plutarch—written by the inhabitants of these cities and the languages they used—Latin and Greek—still terrorize adolescents and delight their teachers. Under the British Empire, men who as youths had their minds stuffed with Greek and Latin conjugations ruled large regions of the world. Whether early Christians spoke Latin or Greek, lived in Alexandria in Egypt or Carthage in North Africa (present day Tunisia), they were formed by Greek or Latin literature.

How Augustine loved Virgil—the “renowned poet,” as he called him. As a student Augustine wept over the death of Dido, the Punic queen who took her own life out of love. Learned Christians read Plato’s

Timaeus before Genesis and Thucydides before the Acts of the Apostles. Clement of Alexandria, a Greek Christian writer who flourished about the year

A.D. 200, effortlessly cited hundreds of passages from Greek poets, philosophers, playwrights, and historians in his writings. To this day he is an unparalleled source of classical citations from lost works, including many precious passages from the writings of pre-Socratic philosophers.

Clement’s writings, like those of other Christian authors in the earlier centuries, were didactic in the broad sense of that term. They were written to instruct and edify, to explain and defend. They would not have been called “literature,” that is, works of the imagination to be read for pleasure at one’s leisure. The first Christian to compose genuine literary works was Aurelius Prudentius Clemens, who was born into a Christian family in Roman Hispania (present-day Spain), in the northeast province of Tarraconensis, in

A.D. 348. As a child of the provincial aristocracy, he received a traditional education, which meant he studied Latin grammar, rhetoric, and, finally, law. When his studies were completed, he pursued a conventional career as an advocate and then was offered a position in the civil administration. What sets Prudentius apart is that he saw himself as a poet by profession. He was not a bishop but a layman with a vocation as poet. In his words, “If I cannot give praise to God by my works, let my soul praise God with my voice.”

Prudentius wrote his poems to be read aloud in a living room or salon or used as a basis for reflection in the solitude of one’s study. Two works in particular stand out. The first is

Peristephanon,

Crown of Martyrdom, a highly original collection of fourteen poems on martyrs. With these poems Prudentius was forging a Christian past—a historical memory for the emerging Christian culture. Besides the great heroes of faith in the Scriptures, Christianity could celebrate “the noble army of martyrs,” as the

Te Deum has it.

Crown of Martyrdom includes poems on martyrs from Spain and the city of Rome, on Peter and Paul, on St. Agnes and St. Laurence, even on a soldier named Quirinius.

Prudentius also wrote the first Christian epic—a long, allegorical poem called

Psychomachia (spiritual warfare), about the internal struggle that takes place in every human soul visited by grace.

Every poet depends on readers who can appreciate and enjoy form as well as content, and his poetry would not have been possible had there not been a long tradition of Latin poetry before the rise of Christianity. Prudentius’ models were not the Psalms or the “canticles” in the Scriptures but the classical Latin poets, and his readers took delight in his metrical virtuosity and verbal allusions to Virgil or Ovid or Horace. One small tribute to his greatness is that, in a library in Gaul, a few generations after his death, his works were kept on a shelf alongside those of Horace. Medieval Latin readers loved his poetry—the

Psychomachia was copied over and over—because Prudentius successfully used traditional forms to express a Christian vision.

Prudentius wrote at a time when the foundations were being laid for a new Christian civilization. Like the architects who set about designing churches for the new Christian society and the artists who took up the challenge of depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints in paint and mosaic, gold and stone, Prudentius put language at the service of the new civilization: He offered his words as a vehicle for the Word. In doing so, he consciously sought to redefine the beautiful by referring to Christ while building on the foundation of the old. Through the luxuriance of his language and the facility of his meter, he achieved a richness of form beyond the reach of earlier Christian writers and a freshness of spirit long forgotten by Latin poets. His work is at once deeply Christian and indisputably musical, and he set Christian tradition on a course that, centuries later, gave rise to a poet as enchanting as Edmund Spenser.

In Prudentius’ day the Latin culture of the Roman world was still intact, and a learned public could appreciate his complicated meter and wordplay. But a time was coming when the cultured society Prudentius could take for granted would go into decline and almost disappear. In that new time, no longer was the Church faced with the task of transforming what had been received; now, its vocation was to preserve and hand on what was being forgotten. People had to be taught to read and write and speak Latin correctly. Consequently, some prescient Christian thinkers turned their attention to grammar, which Dante called

la prima arte. As with Prudentius, the intellectual inheritance of the ancients is evident in the grammarians’ writings, but in a quite different way.

Among early medieval writers who devoted their literary efforts to grammar, the Spaniard Isidore, bishop of Seville, stands out. By the time Isidore was born, in 560, the Roman Empire in the West had long since collapsed. The territories once under its dominion—Italy, Gaul, and Spain—were ruled by Germanic kings. Born into the landed gentry of Cartagena, Isidore was educated at an episcopal school in Seville under the supervision of his brother Leander, the bishop of the city. In the year 600 Isidore succeeded Leander as bishop. Isidore had a profound influence on the Spanish church, its liturgy, its laws, and its relation to the Visigothic kings. But he commands our attention because of his interest in language and in organizing the knowledge that had been inherited from the past.

The work that best represents his genius is known as the

Etymologies. It is a vast encyclopedia that attempted to summarize all branches of knowledge by drawing on the vast reservoir of classical writers: Aesop, Apuleius, Aristotle, Julius Caesar, Catullus, Cicero, Demosthenes, Herodotus, Hesiod, Homer, Horace, Juvenal, Livy, Lucretius, Ovid, Pindar, Plato, Plautus, Quintilian, and Virgil.

The

Etymologies deals with grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, medicine, law, ecclesiastical books and offices, languages, kingdoms, human beings, animals, weights and measures, agriculture, ships, architecture, and clothes. Isidore was engaged in an enterprise not unlike that of my former colleague at the University of Virginia, Eric Hirsch. Hirsch showed that to engage in such an apparently simple task as reading a book or newspaper, one must know certain things. He published a

Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, full of lists of the meanings of words and things and places and persons, and a series of books entitled

What Your Fifth Grader Has to Know.

Isidore also wrote a work entitled

Liber differentiarum sive de proprietate sermonum, a book on the precise meaning of words–that is, the distinctions one must make to use them correctly. One example is the difference between

aptum and

utile: the first refers to something that is temporal, that is, for a time; the second refers to an enduring condition. Similarly, with

alterum and

alius, the first refers to the other of two and the second, to other among many. Comparing

audire and

exaudire, the one means to hear, the other, to listen.

Sanguis and

cruor are two words for blood. One refers to blood as lifeblood; the other, to the blood that flows from a wound. The list is not unlike what one finds in Fowler’s

Modern English Usage: the differences between

sensuous and

sensual,

fewer and

lesser,

further and

farther,

depreciate and

deprecate,

as and

like.

The pedantic grammarian serves as a standard comic figure, but civilization is a thin and fragile thing, and respect for language cannot be taken for granted. Just as stewards of English need to work overtime in our society, so in the sixth century, when spoken Latin was developing into the Romance languages, early medieval thinkers learned that they had to be diligent about grammar, spelling, correct use of terms, and the like.

Isidore, like the famous Roman grammarian and rhetorician Quintilian, recognized that grammar is “the science of correct speech and the interpretation of the poets.” It is not simply a matter of knowing which case goes with which preposition or when to use the subjunctive; it is a study of the features of language and the rules that govern the relation of words and concepts. Grammar teaches students to make distinctions and to use words accurately; it introduces concepts such as analogy and explains the different figures of speech. For Isidore grammar also included etymology: “If you know the origin of a word, you more quickly understand its force. Everything can be more clearly comprehended when its etymology is known.”

Isidore’s work was intended to serve copyists and to make possible the reading of the Bible. But by taking responsibility for elementary education, he also encouraged clear and cogent thinking; this, in turn, lent solidity, authority, and elegance to writing. For Isidore grammar and lexicography were instruments of culture. Indeed, to produce the kind of works he did, drawing on examples from ancient literature, especially in the conditions of his time, required uncommon perseverance and discipline and a well-organized scriptorium for copying earlier books.

Christianity cannot send down deep roots, be handed on from one generation to the next, or flourish without language. Reason is unthinkable without language—a truth that was seen with great perspicacity by J.G. Hamann, the critic of the Enlightenment. “Language is the mother of reason and its revelations, its Alpha and Omega,” he wrote. That our words should follow rules handed down by authorities who are themselves servants of past masters of language provides a fitting preparation for the ordering of common life according to divine commandments handed down from the apostolic tradition.

In the second century Tertullian, the first Christian to write in Latin, already recognized the intimate relation between faith and language. In his day the Latin language and literature were wedded to the gods of Rome. One could not teach Virgil’s

Aeneid without introducing students to the Roman gods. As Tertullian put it, in Roman society literature has an affinity with idolatry. For many this alliance offered a vehicle to upbraid Christians: If they cannot teach literature because its content runs against their beliefs, let them remain unlearned. But, responded Tertullian, learning one’s letters is essential for human life. Christians cannot repudiate secular learning; without language divine learning is ephemeral.

Often, the relation between Christianity and classical culture focuses on the great issues of philosophy. As important as metaphysics might be, Prudentius and Isidore display subtle ways in which Catholic culture draws its moisture from the river of antique culture. Prudentius assumes that the language and forms of Latin poetry can be adapted to the Christian mysteries and create poetry as elegant and refined as that of the great Latin poets. Facing a different challenge, Isidore of Seville returns to basics, not only providing a reservoir of knowledge for the medieval world but also molding the linguistic and conceptual categories that shape literary and intellectual life. And, lest the point be forgotten, this priceless inheritance is the work of a Catholic bishop.

At the University of Virginia, in old Cabell Hall—an auditorium used for classical concerts—a large picture, about forty feet in width and perhaps thirty feet high, dominates the stage. Wherever one sits in the auditorium, there is a good view of the picture; during a concert one can view it throughout the evening. The painting is a copy of Raphael’s

School of Athens, a work created for the papal apartments in Rome in 1510–1511, when the artist was in his late twenties. It shows a large Renaissance portico with a magnificent barrel ceiling that opens into a spacious hall. In the center, at the top of a few steps, stand Plato and Aristotle, Plato apparently holding the

Timaeus, and Aristotle gripping his

Ethics. Around them on either side are the intellectual giants of ancient Greece—Ptolemy, Archimedes, Euclid, Diogenes, Epicurus, Parmenides, Zeno, Socrates, and others. The painting represents the major intellectual disciplines, and it was placed in Cabell Hall to reflect the high ideals to which the university aspires.

Standing alone, the

School of Athens expresses the confidence and self-sufficiency of man to know the truth through his own intellectual efforts. Although Cabell Hall was built long after the death of Thomas Jefferson, Raphael’s painting is a fitting monument to the ideals of the Enlightenment. All that society needs, the painting suggests, can be found in ancient Athens.

But many who sit in Cabell Hall and contemplate the

School of Athens do not realize, unless they have been to Rome to visit the

Stanze di Raffaello, that Raphael painted two pictures that face each other across a modest-sized room. The title of the second picture is sometimes given as the

Disputa, or the

Disputation over the Sacrament , but it is more appropriately entitled the

Adoration of the Sacrament. In the center sits a large monstrance on an altar, with an exposed host of the Eucharist. Above, in ascending order, are the dove of the Holy Spirit, Christ, and, at the apex, God the Father.

In this painting, as in the

School of Athens, most of the figures are identifiable: the four Latin doctors of the Church—Ambrose, Jerome, Augustine, and Gregory the Great; medieval teachers Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure; spiritual leaders Dominic and Francis; artists Fra Angelico and Bramante; and the poet Dante. Flanking Christ are the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist; around them one sees Abraham, Moses, David, Jeremiah, Peter and Paul, John the Evangelist, and other biblical saints. The

School of Athens is laid out on a horizontal axis, with its several groups extending like an animated frieze across the width of the picture. The

Disputa, however, is arranged on a vertical as well as a horizontal axis, and the two axes converge on the host. The world below and the world above communicate with each other, and the entire scene is crowned by a golden light that streams from above.

I had known of Rafael’s

Disputa, but it was not until I visited the

Stanze di Raffaello and saw the two paintings facing each other that I realized why I had always been dissatisfied with the reproduction of the

School of Athens in Cabell Hall. As beautiful and uplifting as it is, taken by itself it is partial and limiting, closed off to the light from above. It offers a frail foundation for a true humanism. “Reason,” wrote Dante, “even when supported by the senses, has short wings.” Raphael’s

Disputa lifts our minds toward things that cannot be seen while putting before us those who, in the words of the Book of Wisdom, obtained “friendship with God” and were “commended for the gifts that come from instruction.”

What is missing from the

School of Athens is not only the light from above, but also men and women of faith, like Prudentius and Isidore, who pursued the arts and sciences because they were believers. They had confidence they could know human things because they had seen divine things. In an individual believer, faith can exist without reason. God does not measure out the supernatural gifts of grace according to IQ. Yet, as a community, the Church needs reason to give faith cultural heft and the density of varied expression in language, whether it be the disciplined, imaginative reasoning that poetry requires, or the elementary, conceptual reasoning of grammar. Reason, for its part, needs faith because the natural powers of the human intellect easily lose sight of their goal, which is the fullness of truth, and can become susceptible to various forms of authoritarianism and intolerance.

The two paintings are complementary and together are a fitting monument to the relation between Christianity and classical culture. Raphael was not a creature of the Enlightenment, pitting reason against faith. He intuitively expressed the “secondarity” of Christian culture, treating the world symbolized by the

School of Athens as a part of the Church’s patrimony, working in tandem with its doctrine that the one God is known as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—as St. Paul taught in front of the Areopagus, quoting from a poet of Athens to draw his listeners toward the truths of faith.

Athens and Jerusalem belong together. Christian culture is never solely religious; it embraces what is best in thought, literature, art, and the sciences—a truth St. Paul saw at the very beginning of the Church’s history. In the Letter to the Philippians he wrote, “Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think on these things.” And so we must and do.

Robert Louis Wilken, chairman of the board of the Institute on Religion and Public Life, is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of the History of Christianity Emeritus at the University of Virginia.