Thursday, December 31, 2009

The Nature of Desire

First Things

“This is the monstrosity in love, lady,” Troilus tells Cressida in Shakespeare’s play, “that the will is infinite and the execution confined, that the desire is boundless and the act a slave to limit.” Human desire, in other words, is doubly infinite: We are perpetually unsatisfied when we get what we want, and we are capable of wanting anything at all.

Suppose Troilus is right. That would mean desire eventually must consume even itself. Indeed, in Troilus and Cressida, Ulysses says precisely that: Since appetite is “an universal wolf, / so doubly seconded with will and power,” it “must make perforce an universal prey, / and last eat up himself.”

I find this understanding of desire immediately plausible. It does not sit well, however, with the way that we Catholic thinkers typically talk about desire—categorizing some desires as natural and others as unnatural. It does not sit well with that most typical of Catholic ideas: natural law. If desire is doubly infinite, as Shakespeare suggests, and therefore self-consuming, what can it mean to speak of any desire as natural?

Of course, if human desire is infinite, then it is, in a sense, entirely natural for us to desire anything we can imagine or conceive. This, in turn, means our desires are naturally open rather than closed, protean rather than formed, awaiting direction rather than already under orders. The range of things on which human desire is focused is, as a matter of fact, infinite, and the plasticity of desire is distinctively human. Consider the desires of your dog, or of the crape myrtle tree in your yard. The desires of these creatures are not infinitely malleable, and the range they are capable of reaching is small.

The nature of human desire, then, is that no particular desire is natural. A full appreciation of human nature—a sort of meta-naturalism—properly denies the natural. And this denial applies even to the drives we have genetically: our urges for sex and food and violence. Even these are capable of formation, reformation, and deformation, to the point of their own erasure. This is why we have Casanovas and celibates, gourmands and hunger artists, torturers and pacifists.

If all this is true, then we ought not to talk as though it were not. You will hear it said, for instance, that the desire for political freedom is a natural human desire, or that heterosexual desire is natural, or that the desire for God is natural (theologians often say this). For that matter, you will hear it sometimes said that it is unnatural to eat horses and snails (the English like to say this, having in mind French culinary tastes), or that parental love for children is natural. Of course, such talk is deeply rooted in tradition, and it’s unlikely that we will stop. But we should understand that, even while we speak this way, we are not in fact more open to any particular configuration of desire than to another.

Or, at least, we have no particularly natural desires now—although, I want to argue, we did before the Fall and will again, after the resurrection to eternal life.

Theologians, especially my fellow Catholic theologians, may find this implausible. But we must begin with the fact that human desire has been deranged. Our desires have moved from order to chaos; they have been opened to the damnable as well as the beautiful. Following hard on the expulsion from the Garden (a place where both human desires and the things on which they focused were arranged beautifully and cultivated in accord with God’s passions), the Bible tells us, Cain envied and killed Abel.

That’s the way the human tale of desire begins—with blood and a hunger for taking from others what they have for no other reason than that they have it. And from this derangement comes, very rapidly, the evils of slavery, rape, genocide, and abortion, together with their many bloody cousins. We lack natural desire because our desires have been removed from their proper arrangement, their properly harmonious response to the fact that we are created beings. After the Fall, we suffer from derangement.

The word derangement can be taken to have two apparently opposed meanings. It has its standard sense of removing arrangement, order, and beauty. But we might also use the word to mean an enclosing, a restricting—a limiting of what is properly a larger range. And this double meaning is reflected in the double derangement of our desires. Derangements in the direction of openness—as when our desires are set free to wander in an open range without limits—necessarily cause a second derangement, this time in the direction of discipline and enclosure.

Our derangedly open desires can be directed to anything at all. But desire never seeks anything, exactly; it always seeks something in particular, though that something might be almost anything. Our sexual, gastronomic, and intellectual appetites are unbounded in what they might desire, but they will eventually focus on some particular desire. For these appetites to be configured, they will have to be narrowed, disciplined, and restricted—that is, deranged in the second sense of the word—from the infinitely open range in which they wander.

This configuration happens inevitably. The question, then, is not whether it will happen, but how, and whether the configuration will be beautiful or ugly. Our appetites for one another (to take just one example), derangedly open as they are now, may be configured toward necrophilia, in which we seek others only as dead.

Or they may be configured toward love, in which we seek others as the particular images of God that each of them is. Or they may be configured anywhere in between. The second derangement, the narrowing one, may aim at a reversal of the first derangement or at its intensification.

Consider hunger. This would appear an innate drive: The sucking reflex of the newborn is something close to a human universal. Still, that drive is almost weightless and formless. It floats nearly free of response to and desire for any particular food. Our hungers are instructed and formed over time by careful nurture. The breast is offered to newborns, and their positive responses to it and its gift of milk are encouraged.

As they grow, children experience their tastes being formed by local habit, custom, and discipline until they become, for instance, adults who appreciate and desire a dozen raw oysters washed down with a crisply citrus-tinged Pinot Gris and who are revolted by a dinnertime offering of roast cat. Or they may become eaters who are disgusted by cheese while eager to eat plantain fried in peanut oil. Every adult eater has gastronomic appetites of fantastic complexity, and every particular feature of that complexity has, among the necessary conditions for its existence, a local catechesis. None of these tastes is natural.

Consider, too, our desire to speak—the appetite for language, for responding to the words of others with words of our own. The catechetical story is the same, whether the children are speakers of Italian, with a taste for writing and reading sestinas, or speakers of English, with a taste for the rhythms of rap. Particular desires for words get configured in a vast edifice of culture, education, and native tongues. As with particular gastronomic choices, configured verbal desires that give delight to some will bore or disgust or puzzle others.

A useful example for understanding this distinctively human feature of desire is the fact of excess. To say of human desires that they are excessive is, first, to repeat that they are open to almost infinitely varying configurations. But it is also to focus attention on the insatiability of desire:

The human effort to configure and reconfigure and extend and elaborate desires is constantly transgressive exactly because it is excessive. Gastronomic desire does not find rest in adequate nutrition. If it did, there would be no chefs, no restaurants, no shelves groaning with diet and recipe books. Sexual desire does not find rest in procreation and loving intimacy. If it did, there would be no adulterers, no pornography, and very little romantic poetry.

The question, then, is how we should discriminate among the configurations of our excess. Which should we encourage, and which discourage? Almost all of us have been catechized—the Christian word is appropriate—in such a way that we have a meta-appetite, an appetite for disciplining both our own appetites and those of others into particular configurations.

Most parents, for instance, prefer to catechize out of their toddlers a desire to display and share their own excrement, a desire that many toddlers show at one time or another. Most teachers work hard to encourage the habits of mental discipline that they think will nurture the development of particular desired skills—literacy, say, or logic. At the same time, teachers work hard to discourage habits that will hinder the development of these skills. And doctors strive to change patterns of appetite, most generally those for a style of life directly productive of disease and death.

Similarly, we often find our own adult appetites in need of reconfiguration, and so we catechize ourselves—whether over something as trivial as an appetite for nicotine or as important as an appetite for self-aggrandizement. Judgments of these kinds, and the catechetical activities that go with them, are normative: They imply an understanding of what human flourishing and human corruption are like. Christians are like everyone else in this. We believe that Jesus Christ came so that we might have life and have it more abundantly. This can be paraphrased without significant loss, except in pithiness, by saying that Jesus Christ came so that our appetites might be configured in some particular way, our desires lent a certain weight—a weight that will turn us from death and fit us for life.

Each particular configuration of appetite has a temporal impetus: It is an element in a habitus, a mode of being in the world, that disposes people to move along its track. There is no inevitability about such movement. It is possible for a well-established habitus to be suddenly and radically reconfigured: Drunks may suddenly cease to drink, the generous may become miserly, and the violent may become peaceable. But this is not the usual story. Usually we continue moving in the direction we are heading.

The ten-year-old child living in Japan is likely to become a more proficient and polished user of Japanese. The man practiced at inflicting pain on others will, in the right context, become even more practiced. The weight of our catechized appetites drags us in a certain direction: The eyes of the glutton follow the food, while those of the devout seek the traces of God.

There is always, in such habits, an implied goal, which is the full development of the habit’s tendency. Christians, of course, believe that even good appetites cannot be developed fully on earth; they find their full and final development only when we see God face to face and know as we are known. Indeed, where the adjective natural is typically used to modify some pattern of appetite, we Christians might do well to substitute a phrase such as to be cultivated in response to divine gift.

Applied to “natural desire” for God, the substitution works well: The desire to know and see God is a configuration we can nurture or oppose. It can flourish or wither because of what we do or refuse to do, and its cultivation is undertaken with an eye to its heavenly result. To desire God is good for us because it prepares us for intimacy with him, which is what we are created for. To configure our desires in such a way that the desire for God becomes progressively less possible for us is to make ourselves less than we should be. In its extreme case, it is damnation.

Christians often say that human beings are disposed to configure appetite in a God-directed way, but we are, in fact, no more disposed to configure our desires that way than any other. This is, in part, why it is improper to speak of our desire for God as natural to us. That desire is just one configuration possible for us; it is no more natural to us than its opposite, which is a desire for the lack that is God’s absence. The cultivation of the desire for God, then, is not a human work independent of God; it is an instance of responsive gratitude to the gift of the very possibility of action.

An interesting question is whether this openness—this inchoateness of desire, this readiness for formation and malformation—is a good thing or a bad thing about us. Is this feature of human existence after the Fall something to be lamented and corrected, or are there features of it that warrant rejoicing—features that make it possible for us to be more fully conformed to God?

In Eden, before the Fall, human desires were not inchoately open in the way they are now. Adam and Eve’s desires were focused on God without need for catechesis, and the desire for God was as natural to them as a heartbeat. An inevitable concomitant of this natural focus, however, would have been a reduction in the range of desire’s texture and possible formation. There would have been neither need nor occasion for the range of gastronomic, verbal, or sexual appetites that are unavoidably open to us now.

The same is true in heaven. The saints’ natural desires are indefectibly fixed on God, formed in the single and maximally beautiful shape of praise. Desire’s heavenly range is, therefore, in one sense, very small: tightly aimed at a single focus. But because the Lord is in every sense infinite, desire’s removal from the open range of possibility that exists here below is not, in fact, a derangement in the direction of loss but, rather, a focus in the direction of infinite gain.

Like Adam and Eve, the saints in heaven have a natural desire for God, but the grammar of the faith requires us to say that there is, nevertheless, a deep difference between Edenic desire and heavenly desire. The difference is not of range but of history—a history that has intervened between paradise and heaven; a history of sin and death, violence and blood; a history in which we are fully implicated.

The absence of tears in heaven—an absence for which there is deep scriptural warrant—does not mean that this history has been erased or forgotten. The weight of it remains because the events that constitute it are real; it is not a shadow play that can be erased by heaven’s radiance. Those who love God in heaven are healed sinners; they include killers and rapists and torturers. Those who dwelled in the paradise at the beginning had not yet sinned and were not yet soaked in blood violently shed.

God’s embrace of each kind of lover is, therefore, correspondingly different. If it is true that there is more heavenly rejoicing over the lost sheep that is found than over the sheep that have not strayed, God’s embrace shows one important sense in which the history that began with the eating of forbidden fruit in the Garden and that will end in the heavenly city is a good one. God’s embrace of each kind of lover is a way of explaining Adam’s sin, and the consequent removal from us of a natural desire for God, as a felix culpa, a happy fault. To say this neither explains nor justifies sin and death. It simply indicates one thing that follows from the Fall’s derangements that should not be lamented but, rather, rejoiced in.

The derangement of human desire in the Garden opened human desire to an infinite range of possibility by making that desire inchoate. The secondary derangements I have described catechize this inchoateness into a vast variety of particular configurations. Each of these particular configurations is, to some extent, damaged, blood- and violence-threaded, idolatrous, lured by lack and absence.

But not every particular configuration is deranged to the same extent. My desire to sing the Sanctus and to receive the body and blood of Christ in humility, in the company of my brothers and sisters in Christ, is not, in these respects, on a par with my desire to dominate by intellectual violence my brothers and sisters in the university. I’ve been catechized into both desires, and both are alive and active in me, but one conforms me more closely to God, and the other damages me by separating me from God.

Catechized, secondarily deranged desires are, then, theoretically locatable in a hierarchy of goodness, although never easily and never without qualification and ambiguity. Among the products of desire deranged are some goods that otherwise would not have been. Consider the singing of a Bach cantata, or the flying buttresses of a Gothic cathedral, or the poetry of George Herbert, or the embrace of lovers long separated, or the gift of time and love to the dying, or the Christian assembly on its knees as bread and wine are consecrated on the altar. All of these fit with desires well catechized and divinely beautiful, and all of them would not have occurred without the Fall.

Such goods will, in some fashion, be taken up into heaven. Their beauty and complexity and order is the reason our theological rejection of the ordinary concept of natural desire is a lament linked with joy.

Catholic theologians and Thomistic philosophers will object to this understanding of the human situation, and their objections must be taken seriously. But consider this: Among the strongest currents of thought these days is one that encourages us to discover who we are and to act accordingly—to gaze with the inward eye on our glassy essence and respond to what we find there. That gaze yields a vast range of identities: of gender and sex and ethnicity, of trait and temperament and passion. If what I have argued is right, when we attempt to discover who we are in that way, we find only phantasms—creatures of the imagination that wither when we turn our imaginations away from them.

This rejection of the language of natural desire opens to us, instead, the truth that we are creatures—inchoate, unformed, and hovering over the void from which we were made—who must seek either to return to that void or to find happiness in the arms of the one who brought us forth from it. There is no glassy essence to discover; there is nothing but an unformed gaze that receives form only by looking away from itself and receiving the gift of being looked at by God.

Paul J. Griffiths holds the Warren Chair of Catholic Theology at Duke University’s Divinity School. This essay is adapted from his October 2008 lecture inaugurating his tenure.

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

So Tired of Myself at Christmas

Scriptorium Daily

The Romans built roads, the Greeks did philosophy, Americans don’t sleep much.

Consuming worthwhile entertainment alone is a full time job: Netflix is calling me to watch the complete Shakespeare now. Add to that the temptation of the guilty pleasures of the new Dr. Who (the best new series of the last three years), working out at the gym, and reading the latest James Scott Bell novel and sleep must go.

Of course, I don’t get to do all those great things very often, because I am lucky to have a job I love. This means that there is no end to the productive stuff I can do! Technology means that I can answer e-mail, work on a book project, or fix a spreadsheet on a day off at Disneyland!

If you have never thought about Quine in line for Space Mountain, you have not lived the multitasking life to its fullest. It really is fun. Solve a knotty problem in epistemology and then scream on a roller coaster.

There is a good side to all of this . . . a happy side, but also a tiring one.

The problem is not fundamentally that I am tired and it would be no revelation to any American that most of us are weary. You can find a jillion web sites urging us to sleep. The problem I think is that too much doing can lead to romantic failure.

We become massively self-centered and there is no love where self is king.

Even defining the problem as “my being tired” misses the point, because it is still all about me. Sleep becomes one more entertainment option (wait until someone masters giving us dreams!) or one more health choice so that we can do more play and work.

Romance requires concentrated time spent on another person with our “A-game” being horded for them. I sleep so that I can be witty for her, I read so there is another anecdote for her, I work to earn her respect. Romance demands rest so that we can give the beloved our best.

Our “tiredness” then is mostly of self.

Christmas is a chance, a blessed chance, to escape this madness. December 25 is the one day most of us cannot be expected to work and should not be doing things just for self. Family is here. Friends are near. We must stop away from the screen and look at incarnate people to properly celebrate the Incarnation.

It is easy. Or it should be.

The diabolical business, more specials on television, more shopping, more consumption for self, that pops up at Christmas bids to ruin it all, but we can stop.

We can today step away from business, self-promotion, self-improvement, and self-centered entertainment and play Legos with our kids. This would be such a massive improvement for most of us that it is tempting to stop there with the Hallmarkian injunction to love others.

But Jesus was too wise to stop with telling us to love our neighbors with the care we give to ourselves. He pointed out that we must love God, not the God who ends up agreeing with us on everything, but the personal God outside our heads. Our neighbors we can choose and our families we might be able to bend to our will, but the Creator God is beyond our power.

The glorious thing about the God of the Bible is that He stubbornly refuses to the change His unchanging Word to fit the times or my mood. Of course, the consumer culture has created a false god, a Santa Deity, who is a reflection of our moods and who affirms us at every turn, but this is just another entertainment option for those with a taste for religious fun.

I am talking about Jesus. Bethlehem is not a little town in my mind, but a real place in Palestine. The cross was not a piece of costume jewelry for my neck, but an instrument of government sanctioned torture. You know you have found the real God when He, like any real person to be loved, makes irritating, but just demands.

He commands me to be chaste. He commands me to love my enemies. He commands me to joy that lies outside of myself.

It is all so annoying until I do it and then it makes me happy. Oddly, this is the final blow to me focus on self, this divine happiness.

If it just made me miserable, it would be easier! I could then develop a feeling of self-sacrifice and nobility in myself, but instead it points out the folly of my life. Self-centered consumerism has made me tired, but much of it was generated by trying to avoid obedience to God’s commands and to simple duty. When I do my duty, stop thinking of my own pleasure, I get pleasure, but then I cannot be sure that I have become humble and giving at all!

My obedience may just be for my own good!

This means I must stop thinking (endlessly thinking) about my own virtue, my own duty, my own charity and think of God. God will command me to think of others and serve them. He will command me to rest from all my work on at least one day of the week.

He will demand I focus on people the way I wish they focused on me.

I will be rested to give Him my best, so that my talking to Him does not end in my falling asleep.

For me the Holiday started on Friday. Today is the first day of a week off . . . for which I am most thankful . . . but most of us will at least get the Day. We can make it a Day for Him and from Him to others or we can try to amuse ourselves.

We will be disappointed in the second, but blessed in the first.

Now I shall go nap, perchance to dream, what dreams may come? God knows best.

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Question 138: Divine Sovereignty and Quantum Indeterminism

ReasonableFaith.org

Question:

Dear Dr Craig,

I just have a question concerning quantum mechanics, God's foreknowledge and God's foreordination.

Given that quantum events are genuinely indeterminate, do you think it is possible for God to know the outcome of these events without controlling them? And is it possible for God to not only know, but also to foreordain, the outcome of certain quantum events without controlling them? And if so, how?

Any help on this issue would be great!

Thanks a lot,

Lucy

Dr. Craig responds:

Great question, Lucy! The answer is: Yes, via His middle knowledge! Let me explain.

Christian theologians have traditionally affirmed that in virtue of His omniscience God possesses hypothetical knowledge of conditional future contingent events. He knows in advance, for example, what would have happened if He spared the Canaanites from destruction, what Napoleon would have done had he won the Battle of Waterloo, how your neighbor would respond if you were to share the Gospel with him.

Hypothetical knowledge is knowledge of what philosophers call counterfactual conditionals, or simply counterfactuals. Counterfactuals are conditional statements in the subjunctive mood. For example: "If I were rich, I would buy a Mercedes;" "If Goldwater had been elected President, he would have won the Vietnam War;" "If you were to ask her, she would say yes." Counterfactuals are so called because the antecedent and/or consequent clauses are typically contrary to fact: I am not rich; Goldwater was not elected President; the U.S. did not win the Vietnam War. But sometimes the antecedent and/or consequent clauses are true. For example, my buddy, emboldened by my assurance that "If you were you ask her, she would say yes," does ask the girl of his dreams for a date and she does say yes.

Christian theologians have traditionally affirmed that God does, indeed, have knowledge of true counterfactuals and, hence, of the conditional future contingent events they describe. What theologians disputed, however, was, so to speak, when God has such hypothetical knowledge. The question here doesn’t have to do with the moment of time at which God acquired His hypothetical knowledge. For whether God is timeless or everlasting throughout time, as an omniscient being He must know every truth there is and so can never exist in a state of ignorance. Rather the "when" refers to the point in the logical order concerning God's creative decree at which God has hypothetical knowledge.

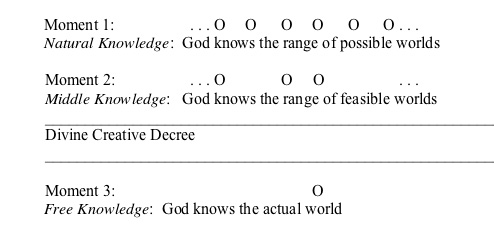

Post-Reformation theologians argued about the logical placement of God's hypothetical knowledge. Everybody agreed that logically prior to God's decree to create a world, God has knowledge of all necessary truths, including all the possible worlds He might create. This was called God's natural knowledge. It gives Him knowledge of what could be. Moreover, everyone agreed that logically subsequent to His decree to create a particular world, God knows all the contingent truths about the actual world, including its past, present, and future. This was called God's free knowledge. It involves knowledge of what will be. The disputed question was where one should place God's hypothetical knowledge of what would be. Is it logically prior to or posterior to the divine creative decree?

Catholic theologians of the Dominican order held that God's hypothetical knowledge is logically subsequent to His decree to create a certain world. They maintained that in decreeing that a particular world exist, God also decreed which counterfactual statements are true. Logically prior to the divine decree, there are no counterfactual truths to be known. All God knows at that logical moment is the necessary truths, including all the various possibilities.

On the Dominican view God picks one of the possible worlds known to Him by His natural knowledge to be actual, and thus subsequent to His decree various statements about contingent events are true. God knows these truths because He knows which world He has decreed to be real. Not only so, but God in decreeing a particular world to be real also decrees which counterfactuals are true. Thus, He decrees, for example, that if Peter had been in such-and-such circumstances instead of the circumstances he was actually in, he would have denied Christ only two times. So God's hypothetical knowledge, like His foreknowledge, is logically posterior to the divine creative decree.

By contrast Catholic theologians of the Jesuit order inspired by Luis Molina maintained that God's hypothetical knowledge is logically prior to His creative decree. This difference between the Jesuit Molinists and the Dominicans was not just a matter of theological hair-splitting! The Molinists charged that the Dominicans had in effect obliterated human freedom by making counterfactual truths a consequence of God's decree. For it is God who determines what a person would do in whatever circumstances he finds himself. By contrast, the Molinists, by placing God's hypothetical knowledge prior to the divine decree, made room for human freedom by exempting counterfactual truths from God's decree. In the same way that necessary truths like 2+2=4 are prior to and therefore independent of God's decree, so counterfactual truths about how people would freely choose under various circumstances are prior to and independent of God's decree.

Not only does the Molinist view make room for human freedom, but it affords God a means of choosing which world of free creatures to create. For by knowing how people would freely choose in whatever circumstances they might be in, God can, by decreeing to place just those persons in just those circumstances, bring about His ultimate purposes through free creaturely decisions. Thus, by employing His hypothetical knowledge, God can plan a world down to the last detail and yet do so without annihilating human freedom, since what people would freely do under various circumstances is already factored into the equation by God. Since God's hypothetical knowledge lies logically in between His natural knowledge and His free knowledge, Molinists called it God's middle knowledge.

On the Dominican view, then, there is one logical moment prior to the divine creative decree, at which God knows the range of possible worlds which He might create, and then He chooses one of these to be actual. On the Molinist view, by contrast, there are two logical moments prior to the divine decree: first, the moment at which He has natural knowledge of the range of possible worlds and, second, the moment at which He has knowledge of the proper subset of possible worlds which, given the counterfactual propositions true at that moment, are feasible for Him to create. The counterfactuals which are true at that moment thus serve to delimit the range of possible worlds to worlds feasible for God.

For example, there is a possible world in which Peter affirms Christ in precisely the same circumstances in which he in fact denied him. But given the counterfactual truth that if Peter were in precisely those circumstances he would freely deny Christ, then the possible world in which Peter freely affirms Christ in those circumstances is not feasible for God. God could make Peter affirm Christ in those circumstances, but then his confession would not be free. Some possible worlds will not be feasible for God to actualize because actualizing them would require that other counterfactuals be true rather than the ones that are—and that is outside God’s control.

So on the Molinist scheme, we have the following logical order (letting the circles represent possible worlds):

Once you grasp the concept of middle knowledge, Lucy, I think you’ll find it astonishing in its subtlety and power. Indeed, I’d venture to say that it is one of the most fruitful theological concepts ever conceived. I’ve applied it to the issues of Christian particularism, perseverance of the saints, and biblical inspiration; Tom Flint has used it to analyze papal infallibility and Christology, and Del Ratzsch has employed it profitably in evolutionary theory.

What begs to be written is a Molinist perspective on quantum indeterminacy and divine sovereignty. For quantum events (if we assume for the sake of argument that indeterminacy is real) are, like human free choices, contingent events. There are, therefore, in addition to counterfactuals of human freedom, counterfactuals of quantum indeterminacy. For example, “If there were a radioactive isotope having such-and-such properties, it would decay at time t.” If statements about indeterminate free choices are either true or false, there’s no reason why counterfactuals of quantum indeterminacy should not be similarly true or false.

In fact, in scientific discussions of something called Bell’s Theorem, which concerns measurements made on paired particles too widely separated to be in causal contact with each other, counterfactuals like “If the position of particle A had been measured instead of its velocity, then the position of particle B would have taken on a correlated value” are usually assumed to be true. Scientists have sometimes remarked that discussions of the counterfactuals involved in Bell’s Theorem often sound like the recondite arguments of medieval theology!

So if counterfactuals of quantum indeterminacy are either true or false, that implies that God’s middle knowledge will include knowledge of just such true propositions. He knows, for example, that if He were to create a physical object in a certain set of circumstances, then specific quantum effects would indeterminately ensue. I think now you can see the implication: by taking into account counterfactuals of quantum indeterminacy along with counterfactuals of human freedom, God can sovereignly direct a world involving such contingents toward His desired ends. Sometimes, these two types of contingents can become interestingly intertwined: for example, God knew that if a grad student in physics waiting in the lab for some event of quantum decay would be delayed going home that evening, he would meet a girl in the hallway whom he would get to know and eventually fall in love with and marry!

So, given quantum indeterminacy, a robust theory of divine sovereignty and providence over the world will require appeal to God’s middle knowledge. For more on this see my book The Only Wise God.

Question 137: Lightning Round

ReasonableFaith.org

Question 1:

Jerry Coyne replies to your recent debate:

"What is especially striking is Craig's failure to tell us what he really believes about how the earth's species got here. It's clear that he thinks God had a direct hand in it, but beyond that we remain unenlightened. IDers believe in limited amounts of evolution. Does Craig think that mammals evolved from reptiles? If not, what are those curious mammal-like reptiles that appear exactly at the right time in the fossil record? Did humans evolve from ape-like primates, or did the Designer conjure us into existence all at once? How did all those annoying fossils get there, in remarkable evolutionary order?

"And, when faced with the real evidence that shows how strongly evolution trumps ID, he clams up completely. What about the massive fossil evidence for human evolution -- what exactly were those creatures 2 million years ago that had human-like skeletons but ape-like brains? Did a race of Limbaughs walk the earth? And why did God -- sorry, the Intelligent Designer -- give whales a vestigial pelvis, and the flightless kiwi bird tiny, nonfunctional wings? Why do we carry around in our DNA useless genes that are functional in similar species? Did the Designer decide to make the world look as though life had evolved? What a joker! And the Designer doesn't seem all that intelligent, either. He must have been asleep at the wheel when he designed our appendix, back, and prostate gland.

"What's annoying about Craig is that he demands evidence for evolution (none of which he'll ever accept), but requires not a shred of evidence for his alternative hypothesis.

"Scientists gain fame and high reputation not for propping up their personal prejudices, but for finding out facts about nature. And if evolution really were wrong, the renegade scientist who disproved it -- and showed that generations of his predecessors were misled -- would reach the top of the scientific ladder in one leap, gaining fame and riches. All it would take to trash Darwinism is a simple demonstration that humans and dinosaurs lived at the same time, or that our closest genetic relative is the rabbit. There is no cabal, no back-room conspiracy. Instead, the empirical evidence for evolution just keeps piling up, year after year."

Care to respond?

Tom

Dr. Craig responds:

I wasn't aware that Coyne, a prominent biologist at the University of Chicago, had taken any cognizance of my debate with Francisco Ayala on "Is Intelligent Design Viable?" His response is precious because it illustrates so clearly exactly what I said in the debate: Darwinists tend to confuse the evidence for the thesis of common ancestry with evidence for the efficacy of the mechanisms of random mutation and natural selection. Did you notice, Tom, how all of Coyne's remarks pertain to the former, not the latter? And yet it was precisely evidence for the latter that I was asking for in the debate. It just amazes me how such brilliant men can be so inattentive to the structure of an argument. As for his other questions, I addressed them specifically in the debate and the public Q & A that followed.

Question 2:

One of your arguments, I think, is that God is a "first cause" (I hope I'm putting it correctly). I have a problem though which I hope you may be able to shed some light on. If time had a beginning in the Big Bang then why should cause and effect still be there "before" time. We really can't know the nature of what was before the big bang in any logical sense so isn't it risky to build and argument on it?

Adam

Dr. Craig responds:

There wasn't anything, Adam, not even God, temporally prior to the Big Bang. God is causally prior to the Big Bang, not temporally prior. Something must be causally prior to the origin of the universe, unless you're ready to believe that something can come into being from nothing. We can know several things about the cause of the universe by means of a conceptual analysis of the notion of a cause of space and time. See my Time and Eternity (2003) for discussion.

Question 3:

Dear Dr. Craig:

First, thank you for your ministry. Reasonable Faith has been an immense comfort to me as I weather the pressure one gets at an Ivy League school to conclude "well, all these smart people say Christianity is false ergo it's probably false." You exemplify why, as C.S. Lewis wrote, very few leave the faith because they have been reasoned out of it by honest argument; indeed, you show that honest argument is on the Christian's side. So, again, thank you very much.

Next, I do have a question I would like you to address. In short, it is how do you respond to the skeptic who says "Very well, I can see that sheer atheism is untenable, but I believe in Spinozism, atheism manque, and that avoids your most serious objections."

As you are no doubt aware from, for example, your debate with Dr. Curley, himself a Spinozist, this is a rather popular opinion these days and is held by some rather brilliant and honest philosophers.

For example, The Last Word, as Victor Reppert notes, is Thomas Nagel's rendition of the "Argument from Reason" that Dr. Reppert writes about in your Companion to Natural Theology. That is, it concludes that "the capacity of the universe to generate organisms with minds capable of understanding the universe is itself somehow a fundamental feature of the universe." Yet, nonetheless, Dr. Nagel (in a quite wonderful and remarkable chapter on his "fear of religion") notes that this "has a quasi-religious 'ring' to it, something vaguely Spinozistic." Yet he maintains that "one can admit such an enrichment of the fundamental elements of the natural order without going over to anything that should count literally as a religious belief." And, of course, there are many other examples, perhaps most notably Albert Einstein.

I have found this view increasingly common among modern philosophers and suspect that it is something of a "new new atheism" for those, like Drs. Curley and Nagel who are too knowledgeable about philosophy to ascribe to the "new atheism."

So, outside of the resurrection (whose implications are plain but nevertheless difficult to make a skeptic face), how do your arguments refute Spinozism? In particular, can you point me to the philosophical necessity of a transcendent rather than immanent God? How could you show Dr. Nagel that his escape hatch is illusory?

Best wishes,

Rob

Dr. Craig responds:

Spinozism, which says that God and the universe are identical, is incompatible with the contingency argument, the kalam cosmological argument, the moral argument, and the ontological argument, not to mention the fact of Jesus' resurrection, so that if any of these arguments is successful, Spinozism fails. For they all conclude to a transcendent reality beyond the universe.

Question 4:

I have just learned that the scientific consensus is that it is perfectly common for ordered structures to appear spontaneously in non-equilibrium processes and that this very mechanism explains both the large-scale structure of the universe and is experimentally confirmed in the Lambda-CDM model which explains the probable the origins of life.

Is there such a consensus and does this model indeed explain the origin of life?

Anthony

Dr. Craig responds:

As a result of gravitation, a universe which is not expanding too quickly or too slowly (a matter of fine-tuning!) will naturally form clumpy structures like galaxies, stars, and planets. But this does nothing to explain the origin of life. Whoever told you it does, Anthony, is just blowing smoke! See Steve Meyer's Signature in the Cell for a nice discussion of current origin of life scenarios.

Question 5:

Hello Dr. Craig,

I am almost finished reading your latest edition of REASONABLE FAITH. I believe that you had stated at one point in the book (and I'm paraphrasing at best) that due to the unobservability of "parallel universes" as proposed by cosmologists who favor String Theory & M-Theory, etc. that ,at least for now, the present Standard Model seems to be the one that you favor. I guess that is pretty much my own estimation at present. But, as all Scientific disciplines seem to merging to bring about a unified Darwinian \ Neo-Darwinian Evolutionary school of thought - and refer to these issues in casual manner & so "matter of factly" . . . my curiosity brings me to ask you if you are a proponebt of evolution & if so\if not could you please expound upon your personal beliefs in this context along with some reaasoning perhaps?

Thank you,

Dan

Dr. Craig responds:

Cosmologists are not leaning toward an evolutionary account of the fine-tuning of the universe. Those who want to defend the alternative of chance usually embrace some sort of Many Worlds Hypothesis according to which all possible values of the fundamental constants and quantities are assumed in the World Ensemble. See my discussion in Reasonable Faith, 3rd ed. For my own views on biological evolution see my Defenders podcasts on Doctrine of Creation and my recent debate with Francisco Ayala.

Question 6:

After your debate with Hitchens... this question was posed.

To give credit this question came from lukeprog over at common sense atheism.

"Dr. Craig,

Tonight you've argued that objective moral values cannot exist apart from grounding them in the traits and opinions of a particular person. Your choice is Yahweh. That seems like an odd way to get objective moral values, but nevertheless, you've elsewhere argued just the opposite: that objective moral values do exist apart from Yahweh.

For example, in your answer to question #61 on your website, you write that abortion is wrong because life has intrinsic moral value that is, moral value within itself, apart from anything outside it, including the opinions of Yahweh. Is this a discrepancy, or have I misunderstood you?"

I am wondering about your thoughts on this matter.

Thank you.

James

Dr. Craig responds:

Good question! My view is that objective moral values are grounded in God's character. Love is virtuous because God is loving. This is not incompatible with distinguishing between intrinsic and extrinsic goods. Something has extrinsic value because it can be used for a purpose. For example, a hammer has extrinsic value because of its utility for human agents. By contrast, persons have intrinsic value in that they are not merely means to be used for some end but are to be treated as ends in themselves. So we might well ask, "But why are human persons intrinsically valuable?" and the answer will be because God is personal.

Question 7:

Hi Dr. Craig, I have a question for you about Jesus and temptation. The Bible teaches in Hebrews 4:15 that Christ felt "our infirmities," and "was in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin." Since Christ lived a perfect, sinless life, and is God in the flesh, how could these "desires" arise in Him? Thanks for your help!

Kevin

Dr. Craig responds:

Since Christ has a true human nature, he was susceptible to all the frailties of humanity, including being tempted to sin. It shouldn't seem incongruous to you, Kevin, that Jesus felt, for example, sexual desire. He was, after all, a man! Being tempted or feeling the desire to sin is not sin.

Question 8:

Dear Dr. Craig,

When I had a recent conversation with my father, I found him to be in serious doubt of whether Christ truly is the way to God or was God incarnate himself. He had 3 reasons for doubt. His first reason is that since he is not God, he cannot know whether Christ was truly telling the truth or not. His second reason for doubt is that due to the recent violence of radical extremists, how do we know whether the radical muslim's faith isn't truly sincere and that he truly is serving God, even in acts of attrocity? His third reason for doubt is that since Christians were undeniably brutal towards other culture only a few centuries ago (Colombus and Cortez) how can we believe we are serving the right God?

Blake

Dr. Craig responds:

I don't find these to be compelling reasons, Blake. (1) Christ is God on the Christian view and so can be trusted. The question is whether we have good grounds for thinking him to be divine. I think we do, in the historical credibility of Jesus' radical personal claims and their vindication by his resurrection from the dead. See Reasonable Faith, 3rd ed. (2) The jihadist most certainly is sincere, but that's no reason to think he is correct in his beliefs. We can assess his claims by examining the grounds for and objections to Islam, as I've sought to do in my debates with Muslims, and by similarly assessing the grounds for and objections to Christian belief. (3) Many people who have claimed to be Christians are hypocrites and not true disciples of Jesus. Tell your father to ask himself the question, "Would Jesus have slaughtered Mayans and Incans?" The answer is obvious. It is He alone who is our teacher and Lord and to whom we look as an example.

Question 9:

I'm am wondering what advice you have for the many Christian PhD students in fields such as philosophy and theology who, due to the current recession in America, face grim job prospects in the academy.

I know of many such students who worked hard to get into top ranked PhD programs and worked very hard to excel in those programs. And their goal, all along, has been to become a professor to help advance the kingdom of God through their research and teaching.

However, I also know of many such students who are now seriously reconsidering whether they should try to become professors, because the job market at the moment is so grim.

Many feel like with the current recession, and the grim academic market, its hopeless to think that they will be able to become professors, so I know of many who are considering abandoning their academic aspirations in order to take up pursuing non-academic careers.

As such, I was wondering what advice you have for the many Christian students who find themselves torn between, on the one hand, trying to pursue the calling of becoming a professor, yet, on the other hand, feel hopeless in the face of the current grim academic market.

Allen

Dr. Craig responds:

Not to be glib, Allen, but people have been saying this for as long as I can remember! As graduate students in the late 1970s we all worried about the grim job market for philosophers and the glut of applicants for every position. My advice to you is to just forget about it. Examine your heart to see what your passion and calling is, and then go for it, trusting the Lord to provide. Those who give up must have either a weak sense of God's calling or else a lack of trust in God's provision. It has been Jan and my experience that God will provide in ways that you couldn't even have imagined at the start! (See Question #83.) So don't let a timorous heart deter you from finding all that God has in store for you!

Question 10:

Dr.Craig,

Thank you for your work! Its been a great help to me. I firmly believe in Jesus and God (although i am new) and with your help and others, im learning to digest what the Bible means.

My question is: Is there anywhere stated that we will have complete recall of our lives on earth and meet God?

I understand this sort of question may be outside of your focus points so i wont hold my breath to hear an answer.

I do however want to thank you again. You do good work and i can only imagine the countless others who stop and solidify what they think or were taught is true, is actually solid and proven facts.

God bless,

Michael

Dr. Craig responds:

Nope, Michael, there's nothing in the Bible to suggest that we shall have total recall in the afterlife. Indeed, it's my view that God may shield us from painful memories.

Question 11:

I've heard it repeated time and time again that not only are we forgiven of our sins because of Jesus, but that also God has forgotten those sins we are forgiven of. I've heard this idea more recently in Dr. Andrew Farley's book 'The Naked Gospel'. However, I'm unable to square this with God's omniscience. I don't believe God can forget anything due to his omniscience, so I don't believe he forgets our sins. However, a lot of apparently well-educated ppeople insist that he can and does.

What is really the case?

Thank you.

Jeremy

Dr. Craig responds:

The language of God's remembering is a Semitic idiom that has to do with God's taking account of or care for. So, for example, when the Bible says that God remembered Israel when it was in bondage in Egypt, it doesn't mean that God suddenly thought to Himself, "Oh, yes! Those people in Egypt!" Similarly, when God is said to remember our sins no more, that doesn't mean God looks at us and wonders, "Sins? What sins?" but that He doesn't reckon our sins against us. Of course, He knows what we did! So there's no incompatibility with omniscience.

Question 12:

First I would like to say how I admire the work you have done. I am a Christian and have a great interest in learning apologetics.

My question comes from the cosmological argument. Using a timeline diagraph which shows that today is currently the last day, therefor time cannot be infinite because something that is infinite does not have an end. Would it not be possible for a skeptic to argue that eternal life is not logical either? Because if we die today, we begin our eternal existence in heaven and something that is eternal cannot have a beginning.

In a conversation with an atheist, he implied that "the universe was changing before time began". I pointed out that the word "change" implies time. If something has changed that means it's current state differs from it's previous state. (time has transpired) This is true for any change; movement, temperature, mass.. etc. Now that I think about it, how does this apply to heaven? If it is eternal would not any act or movement we make there require time to be present?

I would greatly appreciate your expert opinion.

Dan

Dr. Craig responds:

The fact that we shall have dynamic resurrection bodies implies that there will be time in the new heavens and the new earth. We're not going to be like statues. Because of the objectivity of temporal becoming, the past and the future are asymmetrical. An infinite series of past events is an actual infinite, but an infinite series of future events is merely potentially infinite, that is, always finite but increasing toward infinity as a limit. For more see Question #127.

Question 13:

Hello Dr. Craig.... While this question may not be as important as, say, the problem of evil, I still long for an answer so as to provide an answer if need be.

J.P Moreland described the Trinity as being three "whos"(father,son, holy spirit) who all share the same "what"(attributes), and that in the case of the incarnation,Jesus took on a second "what"(humanity), while at the same time retaining his divine attributes. How does this apply to Jesus' divine attribute of omnipresence, given our inability as humans to be in more than one place at a time ?

Thank you for all you do! God bless,

Josh

Dr. Craig responds:

Since Christ has a complete human nature as well as a complete divine nature, he can be said to possess certain properties relative to one nature but not the other. Jesus, then, was omnipresent in his divine nature, but his human nature was spatially circumscribed and limited to various places in Israel. For more, see my chapter on the incarnation in Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview (2003).

Question 14:

Hi Dr Craig.

I just am emailing first to say I am extremely impressed with the time and energy you have devoted into fine tuning (pardon the pun) the Kalam cosmological argument into the well established syllogism it is today. Because of your laborious and incessant dedication it is now widely considered one of the most persuasive and respected arguments for the existence of a Creator.

However I have done research and noticed a few problems with the argument. At first you describe the contradictions that arise when you describe time as this absolute infinite chain of events, unaffected by other dimensions, which I completely agree with. This is well supported by relativity which states that space and time are inextricably intertwined, and time is only a description of activity within space. However premise (2) of the KCA seems to fall flat, since it does a back-flip by stating "the universe began to exist" which heavily implies absolute time! How on earth can the universe begin to exist if there was not an actual time when it did not exist? Most astrophysicists and cosmologists will agree that speculating on what was 'before the big bang' is as meaningless as speculating what is north of the north pole, it literally makes no sense!

Also I think the KCA relies on the fuzzy definition of the word 'universe'. If we define the universe as 'everything that exists anywhere' then God is part of the universe, and since you describe God as timeless and changeless, it refutes (2). If you define it as the 'totality of matter and energy in within space-time' then you might find a way around it, but there is still one more obstacle. It cannot be disputed that the rules of cause and effect are conditional on the space-time continuum, space and time are the medium in which things begin to exist, cease to exist, undergo cause-and-effect and so forth. Isn't it contradictory to say that premise (1), which can be inferred from the cause-and effect can also be applied to the actual universe itself? It reminds me of Russel's Paradox, which talks about the contradictions that arise when you try to make a set a member of itself. It sounds suspiciously circular to me because you are presupposing that there are transcendent rules of cause-and effect that are not contingent on the conditions of time and space!

Finally, I actually came across this cheeky little counter-argument in the form of a Modus Ponens syllogism:

(1) Whatever is sentient has a cause

(2) A personal Creator would be sentient

(3) Therefore, a personal Creator would have a cause

It would be great to hear your thoughts Dr Craig. Thank you very much for taking the time to read my question!

Rhys

Dr. Craig responds:

Forgive my brevity, Rhys! In general relativistic cosmology there is a cosmic time that measures the duration of the universe and which is finite in the past. Beginning to exist does not entail that there was a time at which something did not exist; rather we can say that something begins to exist at t if it exists at t and there is no earlier time t* < t at which the thing existed. The universe satisfies that condition.

The universe may be taken to be space-time and its boundary points, along with the contents of space-time. I most certainly dispute the reductionistic claim that causation is conditional upon the space-time continuum. Don't you think that God could have created angelic beings prior to the existence of physical space and time? Or how about causing timelessly certain abstract objects, if such exist?

As for the syllogism, I see no reason at all to accept premiss (1). By contrast, the causal principle that is the first premiss in the kalam argument is based on the metaphysical intuition that being comes only from being, that being does not originate from non-being. This has been one of the most universally held metaphysical principles in the history of philosophy since Parmenides. God, if He exists, is an uncaused, sentient being, so that the proponent of (1) has to prove that atheism is true if he wants us to accept it.

Plotting Philosophy’s Future

The Common Review

Fifty years ago, on May 7, 1959, the British novelist and scientist C. P. Snow presented the Rede Lecture at Cambridge University titled “The Two Cultures.” The gist of that lecture was that a wide and worrisome gap had developed in Western society between the sciences and the humanities. During and after World War II, Snow had helped conduct interviews of thousands of British scientists and engineers. When he asked his subjects what books they had read, their typical reply was: “I’ve tried a bit of Dickens.” Humanists, he discovered, were equally ignorant when it came to science. He surmised that they had about as much insight into modern physics as did their Neolithic ancestors. Snow put much of the blame for this gap on overspecialization in education. He worried that the house of Western culture had become so deeply divided that it was losing its ability to keep pace with Russia and China and to “think with wisdom” in a world of accelerating social change where the rich “live precariously among the poor.”

A different “two cultures” problem afflicts my own discipline of philosophy, and that is my subject here. But perhaps thinking about philosophy’s future offers us additional insight into the problem that Snow expounded.

When nonphilosophers think about philosophy, they tend to think of it as the history of philosophy. They think of it as a succession of eminent philosophers—along with, of course, the theories those philosophers developed, the texts they wrote, and the movements they inspired. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the perennial favorites. After that, the lists vary according to taste and background, but there are some philosophers who seem never to get on these lists. I have found, for example, that a good way to kill conversations with nonphilosophers is to ask what they think of Willard Quine or Saul Kripke. Because Quine and Kripke are among the most influential American philosophers of the past fifty years, there is reason to wonder why they are not better known outside of philosophy.

One reason for their extramural obscurity is suggested by an imperious quip attributed to Quine, who is alleged to have said: “There are two kinds of philosophers, those who are interested in the history of philosophy and those who are interested in philosophy.” What is intimated here is that the history of philosophy is not really philosophy at all, and that those who pursue such a history are not really philosophers.

Quine knew full well that philosophy departments were expected to conduct research and teach classes in the history of philosophy, but he did not think that service of that kind had much to do with the proper business of philosophy—working out solutions to philosophical problems like, What is there? and, What can we know? In other words, he saw two cultures within philosophy: a can-do culture akin to mathematics and science, and a can-teach culture akin to the humanities.

As a humanist and historian of philosophy, I am tempted to dismiss Quine’s dichotomy as false. I am ready to point out that philosophy, unlike the natural sciences, is the custodian of its own history. Astrophysicists do not think it is their task to write histories of astrophysics. They relegate that task to historians of science—a branch of learning that belongs to the humanities. Philosophers, in contrast, are jealous guardians of this duty and, thus, of their own footing in the humanities. I am also disposed to argue that every chapter in the history of philosophy is an experiment from which we can learn valuable lessons. I am inclined to insist that retelling the story of philosophy can be a powerful way of doing and critiquing philosophy. But these objections may miss a deeper point. Perhaps Quine’s dichotomy should be construed, not as an imperious quip, but as a provocative way of raising an Aristotelian question about the telos—the good—of philosophy. Is the telos of philosophy to solve problems in the manner of the natural sciences, or is it to produce a rich succession of inspiring texts and ideas?

The answer I would like to give is, “Both!” Unfortunately, both alternatives face significant difficulties.

The first alternative is compromised by the fact that, after 2,500 years, philosophers have not reached agreement on the solution to a single, central philosophical problem by means of philosophical methods or argument. Scientists, in contrast, have enjoyed spectacular success in reaching provisional agreement on a wide range of problems and in changing the face of the world with technological applications. I emphasize the word provisional, for agreement in science is always subject to revision when new evidence warrants. If you had asked astrophysicists twelve ago what the universe is made of, they would have said “matter and energy” and referred you to the “standard model” of particles and forces, plus gravity, to describe the details. Today, most astrophysicists will tell you that that ordinary matter and energy make up only about 5 percent of what there is. The rest, they now say, is dark matter and dark energy—elusive stuff whose origin and characteristics remain unknown. Again, this is provisional knowledge, but it is the best answer we can get now, because it fits the relevant data better than any previous answer does. To page back in the history of science for an answer one finds more congenial or inspiring would be foolishness.

The case with philosophy is very different. If you ask philosophers, “What is there?” you will get a multitude of competing answers—including, “It’s a matter of faith,” from Roy Clouser, in The Myth of Religious Neutrality, and Quine’s deflationary analysis, from “On What There Is,” “To be is to be the value of a bound variable.” What you will not get is consensus, provisional or otherwise. Plato complained in The Republic that the quarrels of philosophers discredited the search for wisdom. Two thousand years later, René Descartes drew an even bleaker picture and set out to fix it: “As to philosophy,” he wrote, “it [has] been cultivated for many centuries by men of the most outstanding ability, and that none the less there is not a single thing of which it treats which is not still in dispute, and nothing therefore, which is free from doubt.”

Until a few decades ago, most philosophers nurtured the hope that a revolution in methodology or reforms in standards of practice could change this picture. Ludwig Wittgenstein, whom Bertrand Russell accused of having “the pride of Lucifer,” claimed in 1921, in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, to have “found, on all essential points, the final solution of the problems [of philosophy].”

Eleven years later, the English pragmatist F. C. S. Schiller predicted in Must Philosophers Disagree? And Other Essays in Philosophy that, if philosophers selected for their “open-mindedness, honesty, and good temper” were brought together for “thorough and systematic discussion” under conditions that encouraged mutual understanding and the working out of differences, “they could clear up and clear away a majority of the questions which cast a slur on Philosophy in considerably less than . . . five to ten years.”

Philosophers today are far more skeptical about the chances for philosophical consensus. Few think that agreement on central problems will ever be realized, and some declare openly that philosophical problems are unsolvable (Hilary Putnam, in Realism with a Human Face) or at least unsolvable for human brains (Colin McGinn, Problems in Philosophy).

Given philosophers’ failure to reach agreement and the erosion of hope that this might one day change, the second alternative seems all the more appealing. If the telos of philosophy is to produce a rich succession of inspiring texts and ideas, then it may be a plus that the ingenious worldviews and critical insights that philosophers have developed over the centuries don’t converge. Aristotle’s teleological worldview fell from favor a long time ago, but it remains a majestically coherent way of thinking about ourselves and the world we inhabit. George Berkeley’s arguments that one cannot prove the existence of material substances have never been decisively refuted—not even by Samuel Johnson’s petulant kicking of a rock. But practically no one today accepts Berkeley’s conclusion that all that exists are minds and ideas.

When seen from this angle, the beauty of philosophy is very much like the beauty of poetry. I don’t share John Milton’s theology—though I am sometimes tempted to believe that Satan invented gunpowder—but I am happy to share the world he envisioned. Milton’s world is a kind of refuge, a place where the ways of God and the woes of man are united in poetic intelligibility.

Sometimes I like to slip into Franz Kafka’s world, a nightmarish warren in which earnest people strive in vain to get on with their lives in the face of hopeless odds and cosmic silence. Kafka consoles me for having to commute on the New Jersey Turnpike. I also like to roam James Joyce’s Dublin, where microcosm becomes microcosm and the mundane is transfigured into the mythic. Each of these worlds is remarkable in its own right, but it would be foolish to ask which represents the consensus of poets or the best answer to date in light of relevant evidence.

So why not treat philosophy the same way? Jean-Paul Sartre is among my favorite philosophers. At a time when other philosophers were trying to dissolve the problem of consciousness by reducing it to something else, Sartre put it at the center of his philosophy. In his most important work, Being and Nothingness, he called consciousness Nothingness (le Néant) to emphasize that it is a nonsubstantial being that can exist only as a revelation of something other than itself. What flows from this is a rich worldview that includes, among other things, a radical theory of free will and an original framework for psychoanalysis. Sartre’s world is as atheistic and pessimistic as Milton’s is theistic and hopeful. He closes the main body of Being and Nothingness with these words: “Thus the passion of man is the opposite of that Christ, for man loses himself as man so that God can be born. But the idea of God is contradictory, and we lose ourselves in vain. Man is a useless passion.”

Now, as much as I admire the gritty originality of Sartre’s picture of the world, I find it unconvincing in many respects. I doubt the usefulness of treating consciousness as its own kind of being. I am not convinced that human beings have as much free will as Sartre claimed. I find his psychoanalytic theory naive. I don’t think the concept of God is contradictory. And I believe the pessimism of Being and Nothingness had more to do with temper of the times—the darkest days of World War II—than with anything basic to Sartre’s understanding of the human condition. Sartre himself confirmed this by turning his pessimism into optimism after the liberation of Paris. (His best-known repudiation of his pessimistic assessment of the human condition was a lecture he gave at the Club Maintenant on October 28, 1945, titled “Existentialism Is a Humanism”—that lecture was published a few months later and has since become a classic.) Today the gloominess of Sartre’s writing before 1945 is more likely to elicit smiles than shudders. Perhaps, nothing illustrates this more cheerfully than Danny Shanahan’s 1991 New Yorker cartoon “The Letters of Jean-Paul Sartre to his Mother.” A stocky Madame Sartre stands before an empty rural mailbox. A balloon shows us her thoughts: “Sacre bleu! Again with the nothingness, and on my birthday, yet!”

I have talked about Sartre in some detail as a way of illustrating my own comfort with looking at philosophy through the lens of history and appreciating the power and originality of individual philosophers without worrying about consensus on the solution to philosophical problems. I must confess that I have been looking at philosophy this way for a long time. I started college as a physics major, but after causing a nasty explosion in a chemistry lab, I was counseled to seek a major in which I was likely to do less harm. Philosophy seemed like a safe haven, especially if one stuck to the task of studying and teaching the ideas of eminent philosophers rather of trying to solve philosophical problems.

As the years went by, I realized that you can take the lad out the lab, but you can’t take the lab out of the lad. I never lost my interest in science or my reservations about the ability of philosophy to secure knowledge of the world through methods independent of empirical research. Luckily, my style as a teacher was to celebrate what was best in each philosophical text, and my duties as a dean insulated me from thinking very deeply about anything. But things began to unravel several years ago, when I started to write the book Why Philosophers Can’t Agree. It occurred to me that my historical outlook embodied a historical distortion. One may treat philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and Descartes as akin to great poets, but that is not how they saw themselves. They wanted to answer philosophical questions and to do so in ways that would be persuasive to anyone who was willing and able to follow their arguments. In essence, they agreed with Quine that the telos of philosophy was to solve its problems rather than to celebrate its history.

So the second alternative cannot stand on its own. To do justice to the history of philosophy, we need to acknowledge the priority that nearly all celebrated philosophers have given to problem solving and try to explain why they have failed to reach agreement. My own explanation for the persistence of philosophical disagreement has multiple facets, but I shall mention only two. One is that philosophers often strive to acquire knowledge with characteristics that may be impossible for humans to obtain: knowledge that is categorical, essentialistic, and necessarily true. Another facet is that philosophers lack a process for discarding theories.

Stephen Jay Gould, who was both a biologist and a historian of biology, observed in The Mismeasure of Man, “Science advances primarily by replacement, not by addition. If the barrel is always full, then the rotten apples must be discarded before better ones can be added.” Scientists, unlike philosophers, rely on the testing of empirical predictions extracted from their theories to help them reach agreement on what theories to discard. The process is sometimes messy, and its implementation varies from one science to another, but it works surprisingly well.

Philosophers are not blind to their lack of a comparable discarding process. They joke among themselves about the dean who was chiding the physics department for spending too much money on lab equipment. “Why can’t you be more like the math department?” she asked. “All they ask for are pencils, paper, and wastebaskets. Or, better yet, why can’t you be like the philosophy department? All they ask for are pencils and paper.”

Philosophers generally rely on reasoning and intuition to debate the relative superiority of philosophical theories, but they have never succeeded in developing a process that commands consensus on which theories must be removed from the apple barrel of provisional knowledge and tossed into the wastebasket of history. Perhaps the closest they come is by tacit agreement that some theories are no longer interesting.

Is my explanation surprising? For many philosophers today, it may seem little more than a confirmation of the truism that philosophy isn’t science. But the methodological chasm between philosophy and science, now so familiar to us, is the culmination of a fissure that was still being formed a century ago. It is worth noting that more than 25 percent of Aristotle’s extant writings are biological treatises and heavily empirical in content. Descartes, who was best known in his own day as a mathematician and physicist, dissected animal carcasses to study the interaction of brains and bodies. The arch experimentalist Robert Boyle wrote essays on moral philosophy. David Hume subtitled his Treatise of Human Nature: “Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects.” Had Immanuel Kant died before he wrote Critique of Pure Reason, his most original work would have been his essays in astronomy. Adam Smith was influential as an ethicist, and John Stuart Mill as an economist. William James was trained as a medical doctor and helped found modern psychology. His celebrated treatise The Principles of Psychology (1890), was used as a textbook in both psychology classes and philosophy classes.

Is consensus in philosophy possible? I believe philosophers could achieve agreement on at least some of their central problems, if they were willing to formulate theories that yielded predictions as testable as those in science. How this might work in practice has barely been explored, but a new movement called experimental philosophy has suggested some promising steps. Philosophers often appeal to intuitions as critical links in their arguments, but they seldom explain what intuitions are or why we should rely on them. Experimental philosophy borrows techniques from experimental psychology to gather systematic data on philosophically interesting intuitions, such as what counts as knowledge or under what circumstances a person is morally responsible. It takes armchair pronouncements about what is obvious to all or natural to believe and tests them against the reported intuitions of actual subjects. It sets up experiments that are designed to discover whether variations in intuitions correlate with contingencies such as a subject’s cultural, linguistic, or socioeconomic background.

One of the fringe benefits of experimental philosophy is that it lends itself to student participation. Last fall, I asked the students in my freshman seminar “Morality, Mind, and Free Will,” to join me in developing a survey designed to test John Stuart Mill’s thesis on qualitatively superior pleasures. In Utilitarianism, Mill contends that it is better to be a dissatisfied human than a satisfied pig, better a dissatisfied Socrates than a satisfied fool. In defense of this thesis, he cites the “unquestionable fact” that those who have experienced both prefer the higher to the lower. He says, “No intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool, the dunce, or the rascal is better satisfied with his lot than they are with theirs.” But do these preferences belong to a category of unquestionable fact? My students and I found that the preferences collected by our survey were far more diverse and ambivalent than Mill predicted.

An intriguing question for me is whether philosophers would be willing to let their theories be discarded if those theories yielded false predictions about the intuitions of appropriate subjects. Would an aesthetician be willing to give up a theory of art if it turned out that artists and art professionals had intuitions incompatible with the theory? Clive Bell argued that William Powell Firth’s popular painting The Railway Station was not art because it lacked “significant form.” Would Bell have been willing to give up his theory if painters, museum curators, and art historians found Firth’s painting to be a work of art?

There is considerable interest at present in the naturalization of philosophy and a spirited debate growing about the fruitfulness or futility of seeking wisdom from an armchair. Many philosophers regard the very idea of trading the autonomy of philosophy for the promise of gaining sciencelike agreement as a Faustian bargain. But I think they overlook the riskiness that has always attended originality in philosophy and underestimate the toughness of philosophy’s soul. At the very least, an earnest effort to bridge the methodological gap between science and philosophy would be a thrilling experiment. Admittedly, not all experiments are successful. But this one might open a new chapter in the history of philosophy and help draw cognitive scientists into new areas of fruitful collaboration with philosophers.